Like drowning in slow motion’: Life on the ground at one of America’s hardest-hit COVID-19 hospitals

Fortune,

He was young, polite, and nondescript. Even though he said he felt fine, he looked as though he had just finished running sprints. The symptoms were there: a cough, a low-grade fever, shortness of breath. His oxygen levels were low enough that his doctor admitted him. And thus did Oscar join the ranks of patients at one of the country’s hotspot hospitals, El Centro Regional Medical Center.

When his doctor, Andrew LaFree, the medical director of the center’s emergency department, saw him again a week later, Oscar’s condition had worsened. He looked scared and was struggling to breathe, requiring a machine to assist him. Summoned from the ER to see the patient just a few days after that, LaFree told me, “I had the surreal impression that we were underwater…It occurred to me that the gradual respiratory deterioration of COVID-19 was like drowning in slow motion.”

Oscar died after multiple cardiac arrests. His doctor remains haunted by the fact “that his last memories are of him staring up at my yellow space suit, struggling to breathe, drifting in and out of darkness as we gave him sedatives to put him to sleep.” But the truth is, such has been the near-daily sojourn of the physicians and nurses in this border town in Imperial County, Calif.

For many weeks this summer, the metro area that El Centro Regional Medical Center (ECRMC) serves led the nation in cumulative COVID cases per capita. Unlike many counties with multiple facilities, Imperial has only two small hospitals to serve its community. El Centro Regional was overwhelmed in May and June, its first surge of cases coinciding with an outbreak that occurred in Mexicali, in Baja California. LaFree said patients are often brought by ambulance to the U.S.-Mexico border, dropped off, and then rushed to the nearest hospital—his hospital.

This process, inelegantly referred to as a border dump, is common. According to Adolphe Edward, CEO of El Centro Regional, more than 275,000 Americans live in Mexicali, along with thousands of green-card holders. Many of them choose to cross the border for care at his hospital.

With 24% of people in Imperial County living in poverty, the hospital has long served a diverse patient population which includes those from marginalized communities, with fewer resources and less access. Christian Tomaszewski, the chief medical officer of ECRMC, notes that the county has a 21% unemployment rate and that comorbidities are prevalent, including diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity. There also is a high proportion of elderly residents, who are at higher risk for more severe outcomes with COVID.

All of this may help explain the numbers. Los Angeles Times data shows that the cumulative COVID death rate in Imperial County is more than twice that of any other county in California, and that it continues to rank No. 1 in the state for cumulative cases per capita.

‘COVID fatigue is setting in’

Edward referred to the initial summer wave of cases as COVID 1.0, which he attributed mostly to patients arriving from across the border. But now, as cases rip across the nation, El Centro is seeing its second wave. “COVID 2.0 is a little bit different,” said Edward, with more local, community-acquired infections from superspreader events, like gatherings at skate parks, restaurants, and the like. “COVID fatigue is setting in,” he continued. “I think our resiliency is breaking down.”

Imperial County’s resolve has been tested many times this year. In May and June alone, 1,400 COVID-19 patients came through the ER, of which 497 required admission. Twenty percent of patients were transferred out-of-county, often by helicopter, to other intensive care units around the state, including some hundreds of miles away in San Francisco and Sacramento. By August, nearly 500 patients in total had been transferred out of Imperial County to approximately 90 hospitals.

Those transfers sometimes took three to four days, according to several members of the hospital staff with whom I spoke. One reason for these delays, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, was that several Southern California hospitals improperly denied or delayed accepting COVID-19 patients based on their insurance status, per the newspaper’s review of internal emails.

In our correspondence, Tomaszewski confirmed these actions were a factor contributing to delays in transfers. He added that the state is “trying to guarantee some kind of payment [to the receiving hospitals], but it’s not always working out.” Multiple studies, meanwhile, have shown that the longer patients are boarded in emergency departments awaiting admission, the worse their mortality rate is.

LaFree believes Imperial County is “headed into the fray again.” Numbers began ticking up in mid-October and took off shortly before Thanksgiving, rising more than 180% in a week, per the CDC COVID data tracker. According to Tomaszewski, ECRMC is seeing 30 to 50 COVID patients per day right now, up from 20 to 30 per day just a month ago, and 30% to 45% of admitted patients are COVID-positive. In preparation, the hospital “has doubled, even tripled ICU capacity,” he said, and canceled all elective surgeries for now so they can shift nurses over to care for COVID patients.

“We are surging,” said Tomaszewski. “It will be really bad starting the week after Thanksgiving, I’m sure.”

At a facility as small as El Centro, the scales of balance can tip quickly. In one day last week, a single physician ran four different code blues of pulseless COVID-19 patients, LaFree told me. As ER physicians, we sometimes don’t have a single patient code for a week or two. Are these providers and caretakers superheroes? I think we have our answer.

‘A heck of a lot more prepared’

El Centro Regional is not a tertiary or quaternary care center, meaning it’s not a hospital with extensive specialty service or care. In the past, the hospital had functioned with just six to eight ICU beds. Now, Edward said, the center has ramped up capacity to 20 ICU beds and hired intensive-care specialists from a nearby hospital to help manage all of the critically ill patients. Edward said the plan is to have 32 or even 42 ICU beds shortly; the primary limitation right now is a countrywide staffing shortfall of ICU nurses.

Because of all this planning and preparation, “We’re not going to be headed to the same place this time,” Edward said. “We’ve got Regeneron’s antibody cocktail, monoclonal antibodies, and other sophisticated treatments, so patients are recovering faster. I think the clinical lessons learned earlier are very critical for us because we’re at a much better place in terms of treatment of the disease.” Added Tomaszewski, “We’ve taken advantage of this opportunity to become a critical-care hospital that is offering high-level care.”

In the time of COVID, preparation is everything. Venktesh Ramnath, medical director of critical care and telemedicine outreach at UC San Diego Health, helped build out the expanded ICU program at El Centro. “I think we’re a heck of a lot more prepared than we were during the first surge,” Ramnath said. “Now we have the engine operating in a real, critical care sort of modern approach. We’re much better staffed, we’ve made outcome improvements…So now some patients are actually coming off the ventilators. They are actually getting better.”

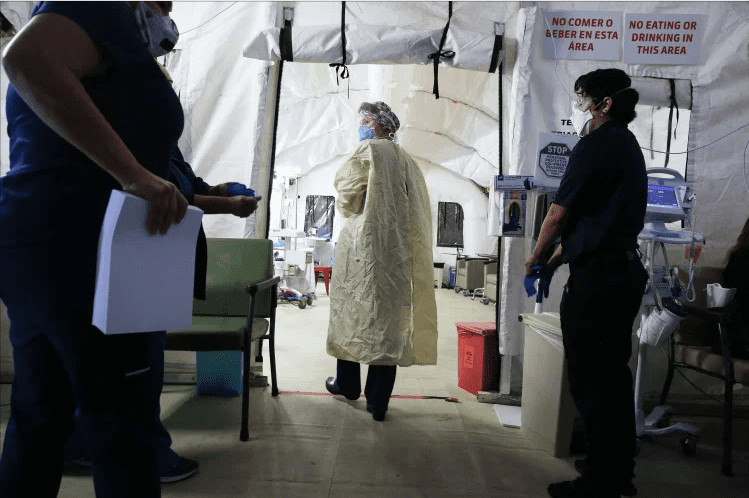

Since the pandemic hit, El Centro Regional has built nine tent structures in its parking lot. Edward, himself retired from the Air Force, noted that the military branch has a saying: “Flexibility is the key to power.” In March, Edward recognized that he needed to build capacity in order to help meet the needs of his county, and the COVID tent is treating approximately 25 patients daily on average in the past week alone.

Another tent is dedicated solely for infusions of bamlanivimab, a new monoclonal antibody that has recently received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration. LaFree said that within days, El Centro “burned through” the 26 doses that the state gave it last week.

Edward has seen projections from now until March of 2021, and they are again troubling. Since his hospital already has been full for most of the last month, his team has just erected a new large tent, a 50-bed medical/surgical unit that will handle non-COVID patients to help decompress hospital bed space.

And transfers of COVID patients likely will continue, with the ICU and hospital at full capacity. Last week, LaFree said, all he could offer one of his COVID patients was transfer to a hospital in Modesto, 520 miles away. His patient refused and went home, only to return 24 hours later “much, much sicker.”

Once again a hotspot, El Centro stands ready but constantly on the verge of being overwhelmed. “What’s scary this time is that it looks like the numbers are blowing up all around California,” LaFree said. “My fear is that we are going to hit a wall transferring patients out this go-round, because other institutions are going to have limited capacity.” LaFree is also concerned about the shortage of available ICU nurses and the acceleration of cases many are predicting following holiday gatherings.

Ramnath has been trying to think outside the box. If staffing issues become a bottleneck, he ruminates that it might be possible to employ an augmented-reality platform (similar to what the Navy uses) for the ICU. “Perhaps you have a less-skilled nurse or physician attending to the patient, but they are coached in real time by someone remotely,” Ramnath said.

It may sound extreme. But with this pandemic, any such solution ought to be at least considered. Very clearly, a vaccine cannot come soon enough. In the meantime, Edward and his team soldier on, treating patients from both sides of the border as COVID 2.0 hits with its full force. Tomaszewski has nicknamed El Centro Regional “The Little Hospital That Could.” Once again, its ability to deliver will be stretched to the limits.