Some COVID Patients Need Amputations to Survive

Impaired blood flow leads to loss of limbs

Scientific American,

In late summer Candice Davis and her brother, Starr, returned to South Philadelphia from a trip to Mexico, and Davis quickly knew that something was wrong. Both she and Starr felt ill, and both subsequently tested positive for COVID-19. But Starr, who had been immunized, experienced only mild flulike symptoms and felt better within a few days. For his unvaccinated sister, a nightmare began to unfold.

Candice, age 30, quarantined for two days but soon noticed that things were worsening. She started to feel her heart “skipping beats.… I was burning up,” she tells me. She called an ambulance. At the Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Davis’s blood pressure plunged to 70/50, and she was diagnosed with myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, caused by infection with the novel coronavirus.

In essence, Davis’s heart was barely pumping. Her treating physician, Nayelah Sultan, says the heart was functioning so poorly that her doctors considered her for a cardiac transplant. Davis also experienced atrial fibrillation, a sudden acceleration of her heartbeat. Her doctors shocked her heart back into a normal rhythm.

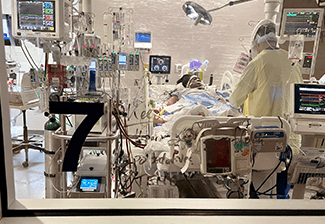

Doctors explained to Davis that she needed to have a breathing tube inserted and to be placed on a ventilator. “I freaked out,” she says, “because I had heard the stories.” After a conversation with her mother, she agreed to the procedure. Hours later, Davis was also placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a heart-lung machine for life support, because she remained critically ill. She was started, too, on an anticoagulant that thins the blood to help prevent clots.

“It was a hot mess,” says Paige Davis, Candice’s mother. Her daughter had lines going in and out of her groin, and she required fasciotomies (cuts made into the muscle) to treat possible compartment syndrome in her legs. “It started with the heart,” Paige says, “but as time went on, everything started to crash.”

Placed in a medically induced coma, Candice Davis doesn ’t remember much from those first few weeks. But she knows what she saw when she awoke: “My arms and my feet, superblack and, like, dead,” she says. “It was terrible.”

Lack of blood flow to Davis’s extremities led to the amputation of one arm above the elbow, one arm below the elbow, one leg below her knee and half her right foot. Her COVID could have killed her, but these procedures saved her life.

Davis’s case shows one of the underappreciated dangers of the disease. As many reports have indicated, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, is associated with a risk of clotting complications such as acute limb ischemia, or ALI. This refers to a sudden decrease in blood flow to a limb, usually because of a blood clot—that is, a thrombosis or embolism—in an artery. When traffic comes to a standstill on one of these arterial thoroughfares, limb viability can be threatened. In Davis’s case, “the prothrombotic state from COVID is probably the thing that made it so, so bad,” says her vascular surgeon Julia Glaser.

How and why these arterial clots form in ALI is unclear, but some experts believe that inflammation and endothelial injury (damage to the inner lining of blood vessels) incited by the virus are likely contributors. “When the endothelium is not working well and its job is to keep keeping blood moving, it’s more prone to clot,” Glaser says.

Arterial blockages can be an embolic phenomenon, in which a blood clot originates from a more proximal source such as the heart, then travels and lodges in a smaller blood vessel, where it can limit or block flow. Alternately, it may be a thrombus, where a blood clot forms and remains at that site within a blood vessel, hindering flow. Life-threatening complications resulting from arterial and venous clot formation may include ALI, heart attacks, deep venous thromboses (DVT), pulmonary emboli (PE), strokes and multiorgan dysfunction, among others.

When I ask about COVID vaccination, Candice, a flight attendant and nursing student, tells me that she was so busy working “that I just wasn’t able to get it.” Now, she adds, “this whole process has brought me to thinking that it’s important to get vaccinated so you don’t lose your limbs and you don’t lose your life. I have lost three of my limbs and half of my foot. It’s scary, and I’m only 30.”

And her brother? “Well, he was vaccinated,” she says. “He’s doing very well. He didn ’t lose any limbs.”

The prevalence of these types of COVID cases is not well-defined, but some of the numbers are worrisome. A Dutch study conducted early in the pandemic of 184 ICU patients found the cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications (PE, DVT, stroke, heart attack or arterial embolism) in COVID-19 patients to be 31 percent. Venous events were noted in 27 percent, while arterial thrombotic events were observed in 3.7 percent. Italian researchers, meanwhile, reported significantly higher numbers of patients presenting with ALI in 2020: 16.3 percent versus 1.8 percent for the same time frame in 2019, prepandemic. The experts with whom I spoke do not describe ALI as a common phenomenon but say it is occurring.

“There was a clear increase in the number of patients presenting with ALI that was associated with COVID infection itself,” says Peter Faries, chief of vascular surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine in the Mount Sinai Health System. He and his colleagues reported on 27 patients who experienced thrombotic events (44 percent were ALI; 26 percent were acute on chronic ALI) out of 6,095 patients with lab-confirmed COVID-19 in March and April 2020. That is an incidence of 0.4 percent. Faries says that the patients were often relatively young and without underlying peripheral arterial disease, unlike most non-COVID patients with ALI. “To date,” he says, “we have not seen COVID-related ALI in a patient that has been vaccinated.”

How Omicron plays into all of this is not yet clear. Clearly more transmissible than even the fast-moving Delta variant, Omicron’s ability to evade immune protection afforded by vaccines is resulting in many breakthrough cases, and experts warn that the unvaccinated remain more at risk of severe disease and hospitalization.

Wes Ely, a critical care specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, recalls drawing blood from a COVID patient who was experiencing a pulmonary embolism. Despite the patient being on maximum blood thinners, “his blood clotted in the syringe before I could get into the test tube,” Ely says. “I ’ve never seen anything like that in my whole life. It was just the craziest thing.” Across the hall, a female COVID patient lost four limbs.

“During our initial response to COVID in early 2020, the amputation rate certainly increased,” says Kenneth Ziegler, chief of vascular surgery at Los Angeles County + University of Southern California Medical Center. “These acute limb ischemias—unless it’s a traumatic incident in a young person, I would not be seeing ALI in patients less than 50 years old except for COVID,” he adds. “But the ones I’ve been seeing for COVID, we were seeing patients in their 30s, 40s.”

Common symptoms of ALI may include an arm or a leg that has abrupt pain, numbness or tingling, coldness, blood blisters, purple discoloration of the skin, black toes or skin mottling. While some COVID patients with ALI have known risk factors or preexisting vascular disease, experts and studies show that others have little or no predisposing factors.

And not all patients with ALI are severely ill, experts say. It can occur in patients who have mild COVID-19 or who have findings related to ALI but are otherwise asymptomatic. Data from 21 patients who had experienced major thrombotic events from COVID-19 infection revealed that most had either mild (38 percent) or moderate (47 percent) disease.

Concerningly, ALI has also been reported in patients who have completely recovered from the virus. And in multiple studies, men who were COVID-positive appeared to be much more commonly affected with ALI than women. A review of 12 studies of COVID-19 limb ischemia found that 79 percent of patients were male. And a study from Spain noted 92 percent of those with ALI were male.

“The mortality associated with infected patients with ALI is much higher than noninfected patients with ALI,” says George Galyfos, a vascular surgeon at Hippocration Hospital University in Athens, Greece. That figure, he says, is about 30 percent, versus somewhere between 5 percent and 9 percent for noninfected patients.

The World Health Organization recommends at least prophylactic doses of blood thinners in critically ill patients admitted to the hospital with COVID-19. For patients who develop ALI, the focus is on saving their limbs, but case management ultimately depends on multiple factors, experts say. Amputation is one such management tool, and in a recently published small study in the Annals of Vascular Surgery, researchers found more than a twofold increase in major amputations in vascular surgery patients after the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. “We do have to save life over limb,” Ziegler says.

Her life dramatically altered, Candice Davis recently began her long process of rehabilitation. Only very recently was she deemed healthy enough to become vaccinated against COVID-19. “They need to get their shots, period,” says Paige Davis, Candice’s mother, when asked if she has anything she wished to share with the public. “It’s not a good sight to watch your daughter lose her limbs. Get vaccinated.”

Hospitalized since August 17, Candice says her primary goal “is getting out of here.” But she also reminds herself to be encouraged “that everything is going to be okay and life is going to get better. I want people to know that serious COVID can be beat.” Sometimes that victory comes at tremendous cost.